I wrote my first Holocaust poem, “Something,” as a teenager. Because it was my first Holocaust poem, “Something” is the first poem on this page.

How did I become an editor, publisher and translator of Holocaust poetry?

In 2003, as editor of The HyperTexts, I published the Holocaust poems of Yala Korwin, a Jewish Holocaust survivor. Yala and I became close friends and together we began to publish translations of Polish and Yiddish Holocaust poems, many by unknown ghetto poets, which had never before appeared in English. I considered it a sacred task, and still do.

In some cases the poems had survived but the names of the poets had been lost. In other cases we had only their initials: M.B. and M.J., for instance.

Yala did the translating and I helped with small suggestions, edits and publication, but all credit goes to her.

With the help of Yala and Esther Cameron, a Jewish-American poet with whom I had a close working relationship at the time, THT was able to publish a number of poems, many by unknown Jewish ghetto poets, written in Polish and Yiddish, that had never before appeared in English. Our early Holocaust pages included those of Jerzy Ficowski, Janusz Korczak, Miklós Radnóti, Wladyslaw Szlengel, and the more famous Elie Wiesel, all published from 2003-2006, along with the work of the ghetto poets.

After Yala died in 2014, one of the most diligent and persevering Witnesses, I took over the task of translating Holocaust poems, as I found them, often by obscure poets who might not have been read in English otherwise, such as the talented boy poet Franta Bass and the little-known but exceptional Ber Horvitz.

I wrote “Pfennig Postcard, Wrong Address” in 2003, under the influence of the Holocaust poems I was publishing, and the poem was published the same year by Esther Cameron in her literary journal Neovictorian/Cochlea. Two years later, in 2005, the poem appeared in the Holocaust anthology Blood to Remember, which I consider my single most important publication, to this day, to have joined so many eloquent voices attesting to mankind’s greatest horror.

In 2005, Yala Korwin became the first poet to have three different THT pages: one for her Holocaust poetry, one for her personal poetry, and one for her visual art. For many years Yala was THT’s most-read poet, a tribute to her talent, her diligence and her perseverance even late in life.

In her 2005 review of THT’s growing collection of Holocaust poetry, Esther Cameron wrote: “Some great voices are gathered here. There is Elie Wiesel, Auschwitz survivor, whose words testify to the persistence of human dignity, and who has become a voice of conscience in his adopted country. The American-born Charles Fishman’s enterprise, on the other hand, is one of evocation and reconstruction, deeply felt. Jerzy Ficowski gives us the voice of Polish Christian conscience. Besides giving us her own testimony of survival and reconstruction, Yala Korwin has translated Ficowski and several unknown ghetto poets, poets who wrote amid the destruction as it was going on, and who did not survive. To me these poems are the most moving of all. But all these testimonies, direct and indirect, are vital. While we can mourn these things together, while we can face together the suffering and the loss, we have not lost the hope of renewal.”

By 2006, we had published so many Holocaust poems by so many different poets that I had to create a Holocaust poetry index to help THT readers find the pages. The same year, I published the work of Takashi “Thomas” Tanemori, a descendent of a proud Samurai family, and a Hiroshima survivor, peace activist, poet and artist

By 2007, THT’s Holocaust pages ranked in the top ten with Google for “Holocaust poetry,” proving the relevance of what we were doing with seekers and searchers. I also published a page of poems about the ethnic cleansing and genocide in Darfur.

In 2008, working in conjunction with the poet, artist, photographer and homeless advocate Judy "Joy" Jones, I published a new THT page called The Holocaust of the Homeless.

The work never ended, as I continue to write, translate and publish poems about the Holocaust and related evidence of man’s inhumanity to man, such as school shootings.

I have kept up the good fight for a half century, not only saying “Never again!” to the Holocaust, but also to the Trail of Tears, American slavery and Jim-Crow-ism, Hiroshima, the ongoing Palestinian Nakba and invasion Ukraine, the plight of the homeless, and school shootings.

I honestly don’t know any living poet who has written more poems, translated more poems, and edited and published more poems on these subjects. The greatest insult of my life has been being labeled an “antisemite” by a group of character assassins. I offer my life’s most important work as a testament otherwise, starting at age 19 with “Something”…

Something

by Michael R. Burch

for the mothers and children of the Holocaust

Something inescapable is lost—

lost like a pale vapor curling up into shafts of moonlight,

vanishing in a gust of wind toward an expanse of stars

immeasurable and void.

Something uncapturable is gone—

gone with the spent leaves and illuminations of autumn,

scattered into a haze with the faint rustle of parched grass

and remembrance.

Something unforgettable is past—

blown from a glimmer into nothingness, or less,

and finality has swept into a corner where it lies

in dust and cobwebs and silence.

Speechless at Auschwitz

by Ko Un

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

At Auschwitz

piles of glasses

mountains of shoes

returning, we stared out different windows.

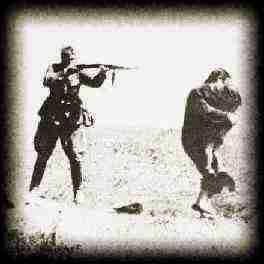

Ko Un speaks for all of us, by not knowing what to say about the evidence of the Holocaust, and man's inhumanity to man. In the photo above American soldiers examine a mountain of shoes left by victims of the Holocaust, many of them children. The photo below is another mountain of shoes at the Dachau death camp.

Ko Un was speechless at Auschwitz.

Someday, when it’s too late,

will we be speechless at Gaza?

—Michael R. Burch

Autumn Conundrum

by Michael R. Burch

It’s not that every leaf must finally fall,

it’s just that we can never catch them all.

Piercing the Shell

by Michael R. Burch

If we strip away all the accouterments of war,

perhaps we’ll discover what the heart is for.

Franta Bass: The Little Boy With His Hands Up

Frantisek “Franta” Bass was a Jewish boy born in Brno, Czechoslovakia in 1930. When he was just eleven years old, his family was deported by the Nazis to Terezin, where the SS had created a hybrid Ghetto/Concentration Camp just north of Prague (it was also known as Theresienstadt). Franta was one of many little boys and girls who lived there under terrible conditions for three years. He was then sent to Auschwitz, where on October 28th, 1944, he was murdered at age fourteen.

The Garden

by Franta Bass

translation by Michael R. Burch

A small garden,

so fragrant and full of roses!

The path the little boy takes

is guarded by thorns.

A small boy, a sweet boy,

growing like those budding blossoms!

But when the blossoms have bloomed,

the boy will be no more …

Jewish Forever

by Franta Bass

translation by Michael R. Burch

I am a Jew and always will be, forever!

Even if I should starve,

I will never submit!

But I will always fight for my people,

with my honor,

to their credit!

And I will never be ashamed of them;

this is my vow.

I am so very proud of my people now!

How dignified they are, in their grief!

And though I may die, oppressed,

still I will always return to life ...

When I say Franta Bass was the little boy with his hands up, I don’t mean that he was the boy in the now-famous picture, but that he wrote for many such little boys, a thought that brings tears to my eyes.

The painting “Auschwitz Rose” above was created by the poet/artist Mary Rae.

Auschwitz Rose

by Michael R. Burch

There is a Rose at Auschwitz, in the briar,

a rose like Sharon's, lovely as her name.

The world forgot her, and is not the same.

I still love her and enlist this sacred fire

to keep her memory exalted flame

unmolested by the thistles and the nettles.

On Auschwitz now the reddening sunset settles!

They sleep alike—diminutive and tall,

the innocent, the "surgeons." Sleeping, all.

Red oxides of her blood, bright crimson petals,

if accidents of coloration, gall

my heart no less. Amid thick weeds and muck

there lies a rose man's crackling lightning struck:

the only Rose I ever longed to pluck.

Soon I'll bed there and bid the world "Good Luck."

Epitaph for a Child of the Holocaust

by Michael R. Burch

I lived as best I could, and then I died.

Be careful where you step: the grave is wide.

I have also published “Epitaph for a Child of the Holocaust” with the titles “Epitaph for a Palestinian Child,” “Epitaph for a Child of Gaza,” “Epitaph for a Ukrainian Child” and “Epitaph for a Child of Darfur.”

Frail Envelope of Flesh

by Michael R. Burch

for the mothers and children of the Holocaust

Frail envelope of flesh,

lying cold on the surgeon’s table

with anguished eyes

like your mother’s eyes

and a heartbeat weak, unstable ...

Frail crucible of dust,

brief flower come to this—

your tiny hand

in your mother’s hand

for a last bewildered kiss ...

Brief mayfly of a child,

to live two artless years!

Now your mother’s lips

seal up your lips

from the Deluge of her tears ...

For a Child of the Holocaust, with Butterflies

by Michael R. Burch

Where does the butterfly go

when lightning rails

when thunder howls

when hailstones scream

while winter scowls

and nights compound dark frosts with snow?

Where does the butterfly go?

Where does the rose hide its bloom

when night descends oblique and chill

beyond the capacity of moonlight to fill?

When the only relief's a banked fire's glow,

where does the butterfly go?

And where shall the spirit flee

when life is harsh, too harsh to face,

and hope is lost without a trace?

Oh, when the light of life runs low,

where does the butterfly go?

Postcard 1

by Miklós Radnóti

written August 30, 1944

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Out of Bulgaria, the great wild roar of the artillery thunders,

resounds on the mountain ridges, rebounds, then ebbs into silence

while here men, beasts, wagons and imagination all steadily increase;

the road whinnies and bucks, neighing; the maned sky gallops;

and you are eternally with me, love, amid all the chaos,

glowing within my conscience — incandescent, intense.

Somewhere within me, dear, you abide forever —

still, motionless, silent, like an angel stunned to complacence by death

or an insect inhabiting the heart of a rotting tree.

Postcard 2

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 6, 1944 near Crvenka, Serbia

translated by Michael R. Burch

A few miles away they're incinerating

the haystacks and the houses,

while squatting here on the fringe of this pleasant meadow,

the shell-shocked peasants sit quietly smoking their pipes.

Now, here, stepping into this still pond, the little shepherd girl

sets the silver water a-ripple

while, leaning over to drink, her flocculent sheep

seem to swim like drifting clouds.

Postcard 3

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 24, 1944 near Mohács, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

The oxen dribble bloody spittle;

the men pass blood in their piss.

Our stinking regiment halts, a horde of perspiring savages,

adding our aroma to death's repulsive stench.

Postcard 4

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 6, 1944 near Crvenka, Serbia

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I fell beside him — his body taut,

tight as a string just before it snaps,

shot in the back of the head.

"This is how you’ll end too; just lie quietly here,"

I whispered to myself, patience blossoming into death.

"Der springt noch auf," the voice above me said

through caked mud and blood congealing in my ear.

"Der springt noch auf" means something like "That one is still jumping."

Translator's Note: In my opinion, Miklós Radnóti, a Jewish-Hungarian poet, was the greatest of the Holocaust poets. He called his final poems "postcards." They were written on his death march and were later discovered in his coat pocket by his wife. She found his body lying in a mass grave. His poetic postcards are stark warnings of the very real dangers created by racism, tribalism and ultra-nationalism.

Cleansings

by Michael R. Burch

Walk here among the walking specters. Learn

inhuman patience. Flesh can only cleave

to bone this tightly if their hearts believe

that God is good, and never mind the Urn.

A lentil and a bean might plump their skin

with mothers’ bounteous, soft-dimpled fat

(and call it “health”), might quickly build again

the muscles of dead menfolk. Dream, like that,

and call it courage. Cry, and be deceived,

and so endure. Or burn, made wholly pure.

If one prayer is answered,

“G-d” must be believed.

No holy pyre this—death’s hissing chamber.

Two thousand years ago—a starlit manger,

weird Herod’s cries for vengeance on the meek,

the children slaughtered. Fear, when angels speak,

the prophesies of man.

Do what you "can,"

not what you must, or should.

They call you “good,”

dead eyes devoid of tears; how shall they speak

except in blankness? Fear, then, how they weep.

Escape the gentle clutching stickfolk. Creep

away in shame to retch and flush away

your vomit from their ashes. Learn to pray.

Published by Other Voices International, Promosaik (Germany), Inspirational Stories, Ulita (Russia), The Neovictorian/Cochlea and Trinacria

Survivors

by Michael R. Burch

In truth, we do not feel the horror

of the survivors,

but what passes for horror:

a shiver of “empathy.”

We too are “survivors,”

if to survive is to snap back

from the sight of death

like a turtle retracting its neck.

Published by The HyperTexts, Gostinaya (Russia), Ulita (Russia), Promosaik (Germany), The Night Genre Project and Muddy Chevy; also turned into a YouTube video by Lillian Y. Wong

Translations of Holocaust poems by Primo Levi

Shema

by Primo Levi

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

You who live secure

in your comfortable houses,

who return each evening to find

warm food,

welcoming faces ...

consider whether this is a man:

who toils in the mud,

who knows no peace,

who fights for crusts of bread,

who dies at another man's whim,

at his "yes" or his "no."

Consider whether this is a woman:

bereft of hair,

of a recognizable name

because she lacks the strength to remember,

her eyes as void

and her womb as frigid

as a frog's in winter.

Consider that such horrors have been:

I commend these words to you.

Engrave them in your hearts

when you lounge in your house,

when you walk outside,

when you go to bed,

when you rise.

Repeat them to your children,

or may your house crumble

and disease render you helpless

so that even your offspring avert their faces from you.

Buna

by Primo Levi

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Mangled feet, cursed earth,

the long interminable line in the gray morning

as Buna smokes corpses through industrious chimneys ...

Another gray day like every other day awaits us.

The terrible whistle shrilly announces dawn:

"Rise, wretched multitudes, with your lifeless faces,

welcome the monotonous hell of the mud ...

another day’s suffering has begun!"

Weary companion, I know you well.

I see your dead eyes, my disconsolate friend.

In your breast you bear the burden of cold, deprivation, emptiness.

Life long ago broke what remained of the courage within you.

Colorless one, you once were a real man;

a considerable woman once accompanied you.

But now, my invisible companion, you lack even a name.

So forsaken, you are unable to weep.

So poor in spirit, you can no longer grieve.

So tired, your flesh can no longer shiver with fear ...

My once-strong man, now spent,

were we to meet again

in some other world, beneath some sunnier sun,

with what unfamiliar faces would we recognize each other?

Note: Buna was the largest Auschwitz sub-camp, with around 40,000 foreign “workers” who had been enslaved by the Nazis. Primo Levi called the Jews of Buna the “slaves of slaves” because the other slaves outranked them.

Primo Michele Levi (1919-1987) was an Italian Jewish chemist, poet, novelist, essayist and Holocaust survivor.

Translations of Holocaust poems by Ber Horvitz

Der Himmel

"The Heavens"

by Ber Horvitz

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

These skies

are leaden, heavy, gray ...

I long for a pair

of deep blue eyes.

The birds have fled

far overseas;

tomorrow I’ll migrate too,

I said ...

These gloomy autumn days

it rains and rains.

Woe to the bird

Who remains ...

Doctorn

"Doctors"

by Ber Horvitz

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Early this morning I bandaged

the lilac tree outside my house;

I took thin branches that had broken away

and patched their wounds with clay.

My mother stood there watering

her window-level flower bed;

The morning sun, quite motherly,

kissed us both on our heads!

What a joy, my child, to heal!

Finished doctoring, or not?

The eggs are nicely poached

And the milk's a-boil in the pot.

Broit

“Bread”

by Ber Horvitz

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Night. Exhaustion. Heavy stillness. Why?

On the hard uncomfortable floor the exhausted people lie.

Flung everywhere, scattered over the broken theater floor,

the exhausted people sleep. Night. Late. Too tired to snore.

At midnight a little boy cries wildly into the gloom:

"Mommy, I’m afraid! Let’s go home!”

His mother, reawakened into this frightful palace,

presses her frightened child even closer to her breast …

"If you cry, I’ll leave you here, all alone!

A little boy must sleep ... this is now our new home.”

Night. Exhaustion. Heavy stillness all around,

exhausted people sleeping on the hard ground.

My Lament

by Ber Horvitz

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Nothingness enveloped me

as tender green toadstools

are enveloped by snow

with its thick, heavy prayer shawl …

After that, nothing could hurt me …

Ber Horvitz or Horowitz (1895-1942) was a talented poet who became a victim of the Holocaust. Born in the West Carpathians, Horowitz translated Polish and Ukrainian writings into Yiddish and wrote poetry in Yiddish.

A Page from the Deportation Diary

by Wladyslaw Szlengel

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I saw Janusz Korczak walking today,

leading the children, at the head of the line.

They were dressed in their best clothes—immaculate, if gray.

Some say the weather wasn’t dismal, but fine.

They were in their best jumpers and laughing (not loud),

but if they’d been soiled, tell me—who could complain?

They walked like calm heroes through the haunted crowd,

five by five, in a whipping rain.

The pallid, the trembling, watching high overhead

through barely cracked windows, were transfixed with dread.

Every now and then, from the loud, tolling bell

a strange moan escaped, like a sea gull’s wailed cry.

Their “superiors” watched, their bleak eyes hard as stone,

so let us not flinch, friend, as they march on, to die.

Footfalls . . . then silence . . . the cadence of feet . . .

O, who can console them, their last mile so drear?

The church bells peal on, over shocked Leszno Street.

Will Jesus Christ save them? The high bells career.

No, God will not save them. Nor you, friend, nor I.

But let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

No one will offer the price of their freedom.

No one will proffer a single word.

His eyes hard as gavels, the silent policeman

agrees with the priest and his terrible Lord:

“Give them the Sword!”

At the town square, dear friend, there is no intervention.

No one tugs Schmerling’s sleeve. No one cries:

“Rescue the children!” The air, thick with tension,

reeks with the odor of vodka, and lies.

How calmly he walks, with a child in each arm:

Gut Doktor Korczak, please keep them from harm!

A fool rushes up with a reprieve in hand:

“Look Janusz Korczak—please look, you’ve been spared!”

No use for that. One resolute man,

uncomprehending that no one else cared

—not enough to defend them—

his choice is to end with them.

What can he say to the thick-skulled conferer

of such sordid blessings?

Should he whisper, “Mein Führer!”

then arrange window dressings?

It’s too late for lessons.

His last rites are kisses

for two hundred children

the wailing world “misses”

but he alone befriended

and with his love, defended.

But dear friend, never fear:

be absolved by a Tear!

Wladyslaw Szlengel (1912-1943) was a Jewish-Polish poet, lyricist, journalist and stage actor. A victim of the Holocaust, he and his wife died during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Janusz Korczak (c. 1878-1942) was a Jewish-Polish educator and children’s author who refused to abandon the Jewish orphans in his care and accompanied them to their deaths at the hands of the Nazis at the Treblinka extermination camp.

Ninety-Three Daughters of Israel

a Holocaust poem by Chaya Feldman

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

We washed our bodies

and cleansed ourselves;

we purified our souls

and became clean.

Death does not terrify us;

we are ready to confront him.

While alive we served God

and now we can best serve our people

by refusing to be taken prisoner.

We have made a covenant of the heart,

all ninety-three of us;

together we lived and learned,

and now together we choose to depart.

The hour is upon us

as I write these words;

there is barely enough time to transcribe this prayer ...

Brethren, wherever you may be,

honor the Torah we lived by

and the Psalms we loved.

Read them for us, as well as for yourselves,

and someday when the Beast

has devoured his last prey,

we hope someone will say Kaddish for us:

we ninety-three daughters of Israel.

Amen

Chaya Feldman was one of 93 girls, ages 14 to 22, who died at the hands of the Nazis by drinking poison at Cracow in 1943.

who, US?

by Michael R. Burch

jesus was born

a palestinian child

where there’s no Room

for the meek and the mild

... and in bethlehem still

to this day, lambs are born

to cries of “no Room!”

and Puritanical scorn ...

under Herod, Trump, Bibi

their fates are the same —

the slouching Beast mauls them

and WE have no shame:

“who’s to blame?”

First they came for the Muslims

by Michael R. Burch

(after Martin Niemoller)

First they came for the Muslims

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Muslim.

Then they came for the homosexuals

and I did not speak out

because I was not a homosexual.

Then they came for the feminists

and I did not speak out

because I was not a feminist.

Now when will they come for me

because I was too busy and too apathetic

to defend my sisters and brothers?

Published in Amnesty International’s Words That Burn anthology.

I, Too, Have a Dream

by Michael R. Burch

I, too, have a dream ...

that one day Jews and Christians

will see me as I am:

a small child, lonely and afraid,

staring down the barrels of their big bazookas,

knowing I did nothing

to deserve such scorn.

―The Child Poets of Gaza, a pseudonym of Michael R. Burch

My nightmare ...

by Michael R. Burch

I had a dream of Jesus!

Mama, his eyes were so kind!

But behind him I saw a billion Christians

hissing "You're nothing!," so blind.

―The Child Poets of Gaza, a pseudonym of Michael R. Burch

Pfennig Postcard, Wrong Address

by Michael R. Burch

We saw their pictures:

tortured out of our imaginations

like golems.

We could not believe

in their frail extremities

or their gaunt faces,

pallid as our disbelief.

They are not

with us now ...

We have:

huddled them

into the backroomsofconscience,

consigned them

to the ovensofsilence,

buried them in the mass graves

of circumstancesbeyondourcontrol.

We have

so little left

of them

now

to remind us ...

Originally published in the Holocaust anthology Blood to Remember, then by Poetry Super Highway, Gostinaya (Russia), Ulita (Russia), Promosaik (Germany), Lone Stars, GloMag (India) and by Archbishop Michael Seneco on his Facebook page and personal website

Translations of poems by Erich Fried

Hear, O Israel!

by Erich Fried

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

When we were the oppressed,

I was one with you,

but how can we remain one

now that you have become the oppressor?

Your desire

was to become powerful, like the nations

who murdered you;

now you have, indeed, become like them.

You have outlived those

who abused you;

so why does their cruelty

possess you now?

You also commanded your victims:

"Remove your shoes!"

Like the scapegoat,

you drove them into the wilderness,

into the great mosque of death

with its burning sands.

But they would not confess the sin

you longed to impute to them:

the imprint of their naked feet

in the desert sand

will outlast the silhouettes

of your bombs and tanks.

So hear, O Israel …

hear the whimpers of your victims

echoing your ancient sufferings …

"Hear, O Israel!" was written in 1967, after the Six Day War.

What It Is

by Erich Fried

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

It is nonsense

says reason.

It is what it is

says Love.

It is a dangerous

says discretion.

It is terrifying

says fear.

It is hopeless

says insight.

It is what it is

says Love.

It is ludicrous

says pride.

It is reckless

says caution.

It is impractical

says experience.

It is what it is

says Love.

An Attempt

by Erich Fried

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

I have attempted

while working

to think only of my work

and not of you,

but I am encouraged

to have been so unsuccessful.

Humorless

by Erich Fried

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

The boys

throw stones

at the frogs

in jest.

The frogs

die

in earnest.

Bulldozers

by Erich Fried

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

Israel's bulldozers

have confirmed their kinship

to bulldozers in Beirut

where the bodies of massacred Palestinians

lie buried under the rubble of their former homes.

And it has been reported

that in the heart of Israel

the Memorial Cemetery

for the massacred dead of Deir Yassin

has been destroyed by bulldozers ...

"Not intentional," it's said,

"A slight oversight during construction work."

Also the murder

of the people of Sabra and Shatila

shall become known only as an oversight

in the process of building a great Zionist power.

The villagers of Deir Yassin were massacred in 1948 by Israeli Jews operating under the command of future Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin.

Erich Fried (1921-1988) was born in Austria. His father died under interrogation by the Gestapo. He fled to London after Germany invaded Austria in 1938. During World War II he became one of the most eminent German poets. Fried’s experiences with racism and fascism led him to oppose Zionism and to support Palestinians, who, like himself, had been driven from their native land into exile.

Translations of Holocaust poems by Chaim Nachman Bialik

After My Death

by Chaim Nachman Bialik

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Say this when you eulogize me:

Here was a man — now, poof, he's gone!

He died before his time.

The music of his life suddenly ground to a halt..

Such a pity! There was another song in him, somewhere,

But now it's lost,

forever.

What a pity! He had a violin,

a living, voluble soul

to which he uttered

the secrets of his heart,

setting its strings vibrating,

save the one he kept inviolate.

Back and forth his supple fingers danced;

one string alone remained mesmerized,

yet unheard.

Such a pity!

All his life the string quivered,

quavering silently,

yearning for its song, its mate,

as a heart saddens before its departure.

Despite constant delays it waited daily,

mutely beseeching its savior, Love,

who lingered, loitered, tarried incessantly

and never came.

Great is the pain!

There was a man — now, poof, he is no more!

The music of his life suddenly interrupted.

There was another song in him

But now it is lost

forever.

On The Slaughter

by Chaim Nachman Bialik

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Merciful heavens, have pity on me!

If there is a God approachable by men

as yet I have not found him—

Pray for me!

For my heart is dead,

prayers languish upon my tongue,

my right hand has lost its strength

and my hope has been crushed, undone.

How long? Oh, when will this nightmare end?

How long? Hangman, traitor,

here’s my neck—

rise up now, and slaughter!

Behead me like a dog—your arm controls the axe

and the whole world is a scaffold to me

though we—the chosen few—

were once recipients of the Pacts.

Executioner!, my blood’s a paltry prize—

strike my skull and the blood of innocents will rain

down upon your pristine uniform again and again,

staining your raiment forever.

If there is Justice—quick, let her appear!

But after I’ve been blotted out, should she reveal her face,

let her false scales be overturned forever

and the heavens reek with the stench of her disgrace.

You too arrogant men, with your cruel injustice,

suckled on blood, unweaned of violence:

cursed be the warrior who cries "Avenge!" on a maiden;

such vengeance was never contemplated even by Satan.

Let innocents’ blood drench the abyss!

Let innocents’ blood seep down into the depths of darkness,

eat it away and undermine

the rotting foundations of earth.

Al Hashechita ("On the Slaughter") was written by Bialik in response to the bloody Kishniev pogrom of 1903, which was instigated by agents of the Czar who wanted to divert social unrest and political anger from the Czar to the Jewish minority.

Chaim Nachman Bialik (1873-1934), also Hayim or Haim, was a Jewish Holocaust poet who wrote in Hebrew. Bialik was one of the pioneers of modern Hebrew poetry; he came to be recognized as Israel's national poet. He combined in a unique way his personal wish for love and understanding with his people’s desire for a homeland.

The Trail of Tears: Native American Poetry Translations by Michael R. Burch

Cherokee Prayer

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

As I walk life's trails

imperiled by the raging wind and rain,

grant, O Great Spirit,

that yet I may always

walk like a man.

When I think of this prayer, I think of Native Americans walking the Trail of Tears.

Sioux Vision Quest

by Crazy Horse, Oglala Lakota Sioux, circa 1840-1877

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

A man must pursue his Vision

as the eagle explores

the sky's deepest blues.

Native American Travelers' Blessing

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Let us walk together here

among earth's creatures great and small,

remembering, our footsteps light,

that one wise God created all.

Native American Prayer

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Help us learn the lessons you have left us

in every leaf and rock.

Native American Proverbs

Before you judge

a man for his sins

be sure to trudge

many moons in his moccasins.

—loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

What is life?

The flash of a firefly.

The breath of a winter buffalo.

The shadow scooting across the grass that vanishes with sunset.

—Blackfoot saying, loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced.

Live your life so that when you die, the world cries and you rejoice.

—White Elk, loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Speak less thunder, wield more lightning. — Apache proverb, translation by Michael R. Burch

No sound's as eloquent as the rattlesnake's tail. — Navajo saying, translation by Michael R. Burch

Knowledge interprets the past, wisdom foresees the future. — Lumbee proverb, translation by Michael R. Burch

The troublemaker's way is thorny. — Umpqua proverb, translation by Michael R. Burch

We will be remembered tomorrow by the tracks we leave today. — Dakota proverb, translation by Michael R. Burch

In closing, let us be remembered for opposing the Trail of Tears, the Holocaust, the Palestinian Nakba, and all similar atrocities, until “Never again!” becomes a reality.

Author's Notes

by Michael R. Burch

What was the genesis, the root cause of the Holocaust? The Holocaust became possible when Nazi Germany denied Jews, Gypsies, Slavs, homosexuals and other human beings the protection of fair laws and courts. All too often the victims were completely innocent women and children, even babies. If German courts had upheld the rights of all people, the Holocaust could never have taken place. Thus the way to keep such things from ever happening again is simple (which does not mean "easy"): the world needs to require every nation to establish equal rights, fair laws and fair courts for all human beings, without exception.

Allowing exceptions to this simple rule invariably leads to terrible misery, suffering and premature unjust deaths. Another name for premature unjust deaths is "murder." White settlers once stripped Native Americans of their human rights and dignity, and soon innocent women and children were walking the Trail of Tears, and dying. White slaveowners once stripped African Americans of their human rights and dignity, and not only did black slaves suffer abomination upon abomination, but it took a terrible Civil War followed by a century of Jim Crow laws, kangaroo courts and public lynchings before the United States finally began to embrace its avowed creed of all men being created equal. Very similar things happened to Australian aborigines and South African blacks, among others. Again, each premature unjust death was a murder. If we add all the horrors together, untold millions of people were murdered. Those murders could have been prevented by fair laws and fair courts.

These problems are only corrected when nations finally abandon racism (I call it the "chosen few sin-drome") and establish equal rights, fair laws and fair courts for everyone. Unfortunately, this is a lesson Israel needs to learn and take to heart today, because Israel's racist laws and courts have led to escalating violence on both sides of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. A Palestinian baby should not—must not—be born with inferior rights to a Jewish baby. When black babies were born with inferior rights to white babies in the United States, the country was ripped apart, because multitudes of white Americans could not bear to see the misery and suffering of so many black children. Today there are many Jewish humanitarian organizations and Jewish individuals who feel the same way about the Palestinians. The existence of more than 200 Jewish organizations that oppose the abuse of Palestinians is proof positive that a terrible problem exists. Why are Jews, Americans and Internationals using their bodies as human shields, to protect Palestinian women, children and farmers in Gaza and the West Bank? The "proof is in the pudding," as the saying goes. If the children of one race need human shields to protect them from the adults of another race, and those adults are wearing military uniforms, then something is clearly wrong. Things only improved in the United States when employees of the government stopped persecuting minorities and started protecting them.

It's time for all Jews of good conscience, all Americans of good conscience, and all the people of the world to confront the simple facts: government-sanctioned racism, unjust laws and unjust courts will always lead to racial violence. Since 1776 human beings have been rightly unwilling to be stripped of their self-evident human rights, and the Palestinians have every reason to demand equal rights for themselves. I am an editor, translator and publisher of Holocaust poetry, not an anti-Semite. I believe in protecting all women and children, and not harming any of them unjustly. I have studied History and have listened to the Witnesses who endured the horrors of the Holocaust, and they tell me that every human being must be protected by fair laws and courts. If it was wrong for the Nazis to strip Jews of their human rights during the Shoah (Hebrew for "Catastrophe"), then it is wrong for Israel to strip Palestinians of their human rights during the Nakba (Arabic for "Catastrophe"). The Shoah is fortunately over; the Nakba unfortunately continues. We must all say "Never again!" to all such atrocities, and never allow a child to be born bereft of equal rights and the protections of fair laws and courts.

War, the God

by Michael R. Burch

War lifts His massive head and turns ...

The world upon its axis spins.

... His head held low from weight of horns,

His hackles high. The sun He scorns

and seeks the rose not, but its thorns.

The sun must set, as night begins,

while, unrepentant of our sins,

we play His game, until He wins.

For War, our God, our bellicose Mars

still dominates our heavens, determines our Stars.

#HOLOCAUST #SHOAH #NAKBA #MRBHOLOCAUST #MRBSHOAH #MRBNAKBA

For an expanded bio, circum vitae and career timeline, please click here: Michael R. Burch Expanded Bio.

Speechless, with tears in my eyes, and a white rose on my mind. The painting of the red rose caught my eye reminding me of the white rose (symbol of the non-violent anti-nazi student movement 'The White Rose') which we wore as children ~ navy blue jumpers with a white rose, or white jumper with a red rose.

The white rose became the symbol for Hans & Sophie Scholl (siblings who were members of the White Rose and were executed in 1943) non-violent conscientious objectors to a brutal regime, rendered speechless... which is kind of happening now.

Indeed, a most important life's work Michael ♥️ 🙏 🌺

I am a poet with few words, and this is truly incredible work. Thank you so very much, Michael. Your poignant words illuminate humanity’s capacity for both unspeakable cruelty and enduring dignity, leaving a profound impact on the soul. These poems remind us to reflect deeply and act resolutely to ensure history’s most devastating lessons are never forgotten. Like many readers, I will need to return here again and again (ad infinitum), for one cannot fully digest such richness in just one sitting. Namaste