Skill of the Irish!

People talk about the "luck of the Irish" but what about their skill at poetry, music and the other arts? Are the Irish the world's most poetic people?

I am dedicating this collection to my friend and fellow poet Martin Mc Carthy.

Did Oscar Wilde write the most beautiful and touching poem in the English language, “Requiescat”? Or was it William Butler Yeats with “The Wild Swans at Coole”? Another personal favorite of mine is “Punishment” by Seamus Heaney, one of the all-time best poems about human nature and man’s inhumanity to man. Was Amergin the first notable poet of the British isles? These are the sort of questions I intend to explore, so let’s dive in…

I will begin, for whatever it’s worth, with my personal ranking of the great Irish poets as poets, not considering prose: William Butler Yeats, Seamus Heaney, Oscar Wilde (primarily for “Requiscat” because I favor one magnificent poem over many good ones), the vastly underrated Louis MacNeice and Ethna Carbery, Thomas Moore, Paul Muldoon, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Beckett, Patrick Kavanagh, Eavan Boland, Derek Mahon, Thomas Kinsella, Austin Clarke, Seamus Cassidy (the pen name of Jim McManmon), James Joyce, Amergin (?).

Martin Mc Carthy recommended John Montague who was “born in Brooklyn, but as Irish as they come, and a truly great poet.” Recommended poems by Montague include “All Legendary Obstacles,” “Tides,” “The Same Gesture” and “Like Dolmens Round My Childhood.” Martin also recommended Michael Longley and Richard Murphy, “two excellent poets by any standard.”

If I have left anyone really good out, it is probably my memory playing tricks on me or not having not read enough of their work to judge it properly. Please feel free to suggest other poets, along with a few of their best poems, in the comments and I will consider adding them here.

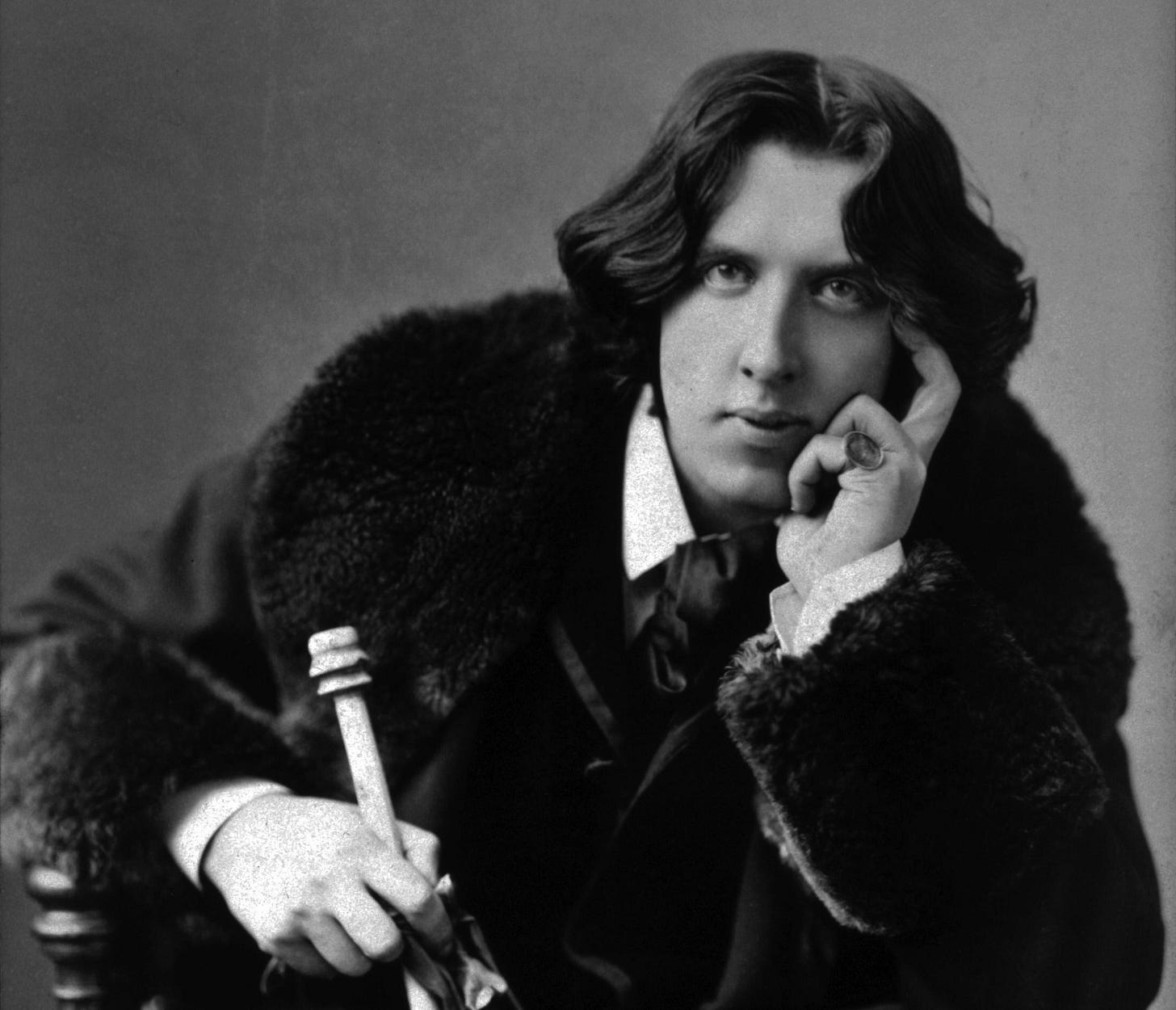

Oscar Wilde may be the most notorious "bad boy" in the annals of poetry and literature, or second only to Lord Byron. Well, and perhaps to his alleged love interest, Walt Whitman. And there are other candidates, like Rimbaud, Shelley and Villon.

In any case, Wilde was flamboyantly gay and outrageously outspoken at a time when polite society was prim, proper and violently homophobic. As a result, the Divine Oscar Wilde was sentenced to hard labor at Reading Gaol and died soon after his release.

Wilde is justly famous for his disdain for dull and dulling conformity, as his witty epigrams attest. But this lovely, wonderfully moving elegy he wrote for his sister Isola, who died at age ten, proves that Wilde was a true poet capable of creating timeless art.

Requiescat

by Oscar Wilde

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

All her bright golden hair

Tarnished with rust,

She that was young and fair

Fallen to dust.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

Coffin-board, heavy stone,

Lie on her breast,

I vex my heart alone,

She is at rest.

Peace, Peace, she cannot hear

Lyre or sonnet,

All my life's buried here,

Heap earth upon it.

It’s hard to imagine anything more beautiful, and certainly nothing more touching.

William Butler Yeats is the most famous Irish poet and his poems of unrequited love for the beautiful Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne have helped preserve her memory. The first poem below is a loose translation of a Ronsard poem, in which Yeats imagines the love of his life in her later years, tending a fire. The second poem, "The Wild Swans at Coole," is surely one of the most beautiful poems ever written, in any language.

When You Are Old

by William Butler Yeats

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

I wrote my poem “Hearthside” imagining W. B. Yeats tending a fire in his later years while thinking about the love of his life.

Hearthside

by Michael R. Burch

“When you are old and grey and full of sleep...” — W. B. Yeats

For all that we professed of love, we knew

this night would come, that we would bend alone

to tend wan fires’ dimming bars—the moan

of wind cruel as the Trumpet, gelid dew

an eerie presence on encrusted logs

we hoard like jewels, embrittled so ourselves.

The books that line these close, familiar shelves

loom down like dreary chaperones. Wild dogs,

too old for mates, cringe furtive in the park,

as, toothless now, I frame this parchment kiss.

I do not know the words for easy bliss

and so my shriveled fingers clutch this stark,

long-unenamored pen and will it: Move.

I loved you more than words, so let words prove.

My sonnet is written from the perspective of an aging, disconsolate Yeats in his loose translation/interpretation of the Pierre de Ronsard sonnet “When You Are Old.” The aging Yeats thinks of his Muse and the love of his life, Maud Gonne. As he seeks to warm himself by a fire conjured from ice-encrusted logs, he imagines her doing the same. While Yeats had insisted that he wasn’t happy without Gonne, she disagreed: “Oh yes, you are, because you make beautiful poetry out of what you call your unhappiness and are happy in that. Marriage would be such a dull affair. Poets should never marry. The world should thank me for not marrying you!”

When Maud Gonne turned down his proposal of marriage, Yeats then proposed to her daughter, Iseult! This is my original poem about another Irish Iseult:

Isolde's Song

by Michael R. Burch

Through our long years of dreaming to be one

we grew toward an enigmatic light

that gently warmed our tendrils. Was it sun?

We had no eyes to tell; we loved despite

the lack of all sensation—all but one:

we felt the night's deep chill, the air so bright

at dawn we quivered limply, overcome.

To touch was all we knew, and how to bask.

We knew to touch; we grew to touch; we felt

spring's urgency, midsummer's heat, fall's lash,

wild winter's ice and thaw and fervent melt.

We felt returning light and could not ask

its meaning, or if something was withheld

more glorious. To touch seemed life's great task.

At last the petal of me learned: unfold.

And you were there, surrounding me. We touched.

The curious golden pollens! Ah, we touched,

and learned to cling and, finally, to hold.

Originally published by The Raintown Review and nominated for the Pushcart Prize

According to legend, Isolde (also known as Iseult and Yseult) was an Irish princess who married King Mark of Cornwall. However, she fell in love with the Cornish knight/minstrel Tristram (also known as Tristan) and in some versions of the story used a love potion to get him; in other versions they was under the same spell. There are different versions of the denouement but they all end badly for the star-crossed lovers. After the deaths of Tristram and Isolde, a hazel and a honeysuckle grew out of their graves until the branches intertwined and could not be parted. It seems the English legend is based on an older Irish legend, The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne. In the Irish legend the aging king Fionn mac Cumhaill takes the lovely young princess Gráinne to be his wife. At the betrothal ceremony she falls in love with Diarmuid Ua Duibhne, one of Fionn's warriors. Gráinne gives a sleeping potion to everyone else, then convinces Diarmuid to elope with her. The fugitive lovers are then pursued all over Ireland by the Fianna. Later tales of the King Arthur-Sir Lancelot-Guinevere ménage à trois are likely descendents of The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne.

If someone held a gun to my headed and demanded that I name the most beautiful poem ever written, this would be my choice:

The Wild Swans at Coole

by William Butler Yeats

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

Upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine and fifty swans.

The nineteenth Autumn has come upon me

Since I first made my count;

I saw, before I had well finished,

All suddenly mount

And scatter wheeling in great broken rings

Upon their clamorous wings.

I have looked upon those brilliant creatures,

And now my heart is sore.

All’s changed since I, hearing at twilight,

The first time on this shore,

The bell-beat of their wings above my head,

Trod with a lighter tread.

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold,

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

But now they drift on the still water

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake’s edge or pool

Delight men’s eyes, when I awake some day

To find they have flown away?

At the other end of the poetic spectrum is the following magnificent poem by Seamus Heaney, who is arguably the greatest poet to have lived in the 21st century and also arguably the language’s best poet since his countryman Yeats and immortals like E. E. Cummings, T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Sylvia Plath and Wallace Stevens relinquished their pens.

Punishment

by Seamus Heaney

I can feel the tug

of the halter at the nape

of her neck, the wind

on her naked front.

It blows her nipples

to amber beads,

it shakes the frail rigging

of her ribs.

I can see her drowned

body in the bog,

the weighing stone,

the floating rods and boughs.

Under which at first

she was a barked sapling

that is dug up

oak-bone, brain-firkin:

her shaved head

like a stubble of black corn,

her blindfold a soiled bandage,

her noose a ring

to store

the memories of love.

Little adulteress,

before they punished you

you were flaxen-haired,

undernourished, and your

tar-black face was beautiful.

My poor scapegoat,

I almost love you

but would have cast, I know,

the stones of silence.

I am the artful voyeur

of your brain’s exposed

and darkened combs,

your muscles’ webbing

and all your numbered bones:

I who have stood dumb

when your betraying sisters,

cauled in tar,

wept by the railings,

who would connive

in civilized outrage

yet understand the exact

and tribal, intimate revenge.

When I founded The HyperTexts around 30 years ago — I forget exactly when — one of the first two poems published was “The Forge” and to this day it remains on THT’s main page and frontispiece.

The Forge

by Seamus Heaney

All I know is a door into the dark.

Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting;

Inside, the hammered anvil’s short-pitched ring,

The unpredictable fantail of sparks

Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water.

The anvil must be somewhere in the centre,

Horned as a unicorn, at one end and square,

Set there immoveable: an altar

Where he expends himself in shape and music.

Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose,

He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter

Of hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows;

Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick

To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

My poem “The Forge” — a sonnet about hammering out sonnets — was both inspired and greatly influenced by Heaney’s famous poem.

The Forge

by Michael R. Burch

To at last be indestructible, a poem

must first glow, almost flammable, upon

a thing inert, as gray, as dull as stone,

then bend this way and that, and slowly cool

at arms-length, something irreducible

drawn out with caution, toughened in a pool

of water so contrary just a hiss

escapes it—water instantly a mist.

It writhes, a thing of senseless shapelessness ...

And then the driven hammer falls and falls.

The horses prick their ears in nearby stalls.

A soldier on his cot leans back and smiles.

A sound of ancient import, with the ring

of honest labor, sings of fashioning.

Originally published by The Chariton Review

“Bagpipe Music” is one of my all-time favorite poems by an Irish bard. I love it for its musicality, cleverness and sparkling wit.

Bagpipe Music

by Louis MacNeice

It's no go the merrygoround, it's no go the rickshaw,

All we want is a limousine and a ticket for the peepshow.

Their knickers are made of crepe-de-chine, their shoes are made of python,

Their halls are lined with tiger rugs and their walls with head of bison.

John MacDonald found a corpse, put it under the sofa,

Waited till it came to life and hit it with a poker,

Sold its eyes for souvenirs, sold its blood for whiskey,

Kept its bones for dumbbells to use when he was fifty.

It's no go the Yogi-man, it's no go Blavatsky,

All we want is a bank balance and a bit of skirt in a taxi.

Annie MacDougall went to milk, caught her foot in the heather,

Woke to hear a dance record playing of Old Vienna.

It's no go your maidenheads, it's no go your culture,

All we want is a Dunlop tire and the devil mend the puncture.

The Laird o' Phelps spent Hogmanay declaring he was sober,

Counted his feet to prove the fact and found he had one foot over.

Mrs. Carmichael had her fifth, looked at the job with repulsion,

Said to the midwife "Take it away; I'm through with overproduction."

It's no go the gossip column, it's no go the Ceilidh,

All we want is a mother's help and a sugar-stick for the baby.

Willie Murray cut his thumb, couldn't count the damage,

Took the hide of an Ayrshire cow and used it for a bandage.

His brother caught three hundred cran when the seas were lavish,

Threw the bleeders back in the sea and went upon the parish.

It's no go the Herring Board, it's no go the Bible,

All we want is a packet of fags when our hands are idle.

It's no go the picture palace, it's no go the stadium,

It's no go the country cot with a pot of pink geraniums,

It's no go the Government grants, it's no go the elections,

Sit on your arse for fifty years and hang your hat on a pension.

It's no go my honey love, it's no go my poppet;

Work your hands from day to day, the winds will blow the profit.

The glass is falling hour by hour, the glass will fall forever,

But if you break the bloody glass you won't hold up the weather.

This original poem of mine was inspired by the Irish potato famine, the musicality of Irish poetry, and songs like “Molly Malone”:

The Celtic Cross at Île Grosse

by Michael R. Burch

“I actually visited the island and walked across those mass graves [of 30,000 Irish men, women and children], and I played a little tune on me whistle. I found it very peaceful, and there was relief there.” – Paddy Maloney of The Chieftans

There was relief there,

and release,

on Île Grosse

in the spreading gorse

and the cry of the wild geese . . .

There was relief there,

without remorse

when the tin whistle lifted its voice

in a tune of artless grief,

piping achingly high and longingly of an island veiled in myth.

And the Celtic cross that stands here tells us, not of their grief,

but of their faith and belief—

like the last soft breath of evening lifting a fallen leaf.

When ravenous famine set all her demons loose,

driving men to the seas like lemmings,

they sought here the clemency of a better life, or death,

and their belief in God gave them hope, a sense of peace.

These were proud men with only their lives to owe,

who sought the liberation of a strange new land.

Now they lie here, ragged row on ragged row,

with only the shadows of their loved ones close at hand.

And each cross, their ancient burden and their glory,

reflects the death of sunlight on their story.

And their tale is sad—but, O, their faith was grand!

My poem "Erin" was inspired by one of my Irish cousins who was a bit of a "wild child" in her youth:

Erin

by Michael R. Burch

All that’s left of Ireland is her hair—

bright carrot—and her milkmaid-pallid skin,

her brilliant air of cavalier despair,

her train of children—some conceived in sin,

the others to avoid it. For nowhere

is evidence of thought. Devout, pale, thin,

gay, nonchalant, all radiance. So fair!

How can men look upon her and not spin

like wobbly buoys churned by her skirt’s brisk air?

They buy. They grope to pat her nyloned shin,

to share her elevated, pale Despair ...

to find at last two spirits ease no one’s.

All that’s left of Ireland is the Care,

her impish grin, green eyes like leprechauns’.

THE CAMELOT CONNECTION

There are many connections between ancient Irish mythology and the later Christianized myths of King Arthur and his knights. Such connections include otherworldly characters like the elvish Lady of the Lake, faeries, and witches like Ceridwen and Morgan le Fay…

Midsummer-Eve

by Michael R. Burch

What happened to the mysterious Tuatha De Danann, to the Ban Shee (from which we get the term “banshee”) and, eventually, to the druids? This poem is an epitaph of sorts for the eldest of the Irish ancestors ...

In the ruins

of the dreams

and the schemes

of men;

when the moon

begets the tide

and the wide

sea sighs;

when a star

appears in heaven

and the raven

cries;

we will dance

and we will revel

in the devil’s

fen ...

if nevermore again.

Originally published by Penny Dreadful

Lament for the Sídhe

by Michael R. Burch

Smaller and fairer

than their closest kin,

the faeries learned only too well

never to dwell

close to the villages of larger men.

Only to dance in the starlight

when the moon was full

and men were afraid.

Only to worship in the farthest glade,

ever heeding the raven and the gull.

The eldest Irish fairies were known as the Aes Sídhe, the Aos Sí and the Sídhe. Because "Sídhe" means "mound" in Irish, they were literally the "people of the fairy mounds." Yeats and others later shortened the term to simply "Sídhe." In my poem the Sídhe avoid their larger, very dangerous kinfolk, and use sharp-eyed ravens and gulls as lookouts, explaining why we never see them.

The Kiss of Ceridwen

by Michael R. Burch

The kiss of Ceridwen

I have felt upon my brow,

and the past and the future

have appeared, as though a vapor,

mingling with the here and now.

And Morrigan, the Raven,

the messenger, has come,

to tell me that the gods, unsung,

will not last long

when the druids’ harps grow dumb.

According to an ancient Celtic myth, the Welsh witch Ceridwen came originally from Ireland, where she was known as the giantess Kymideu Kymeinvoll. She had a magical cauldron with the power to restore dead warriors to life. Bran the Blessed offered Ceridwen safe harbor away from Ireland, where she was greatly feared, in exchange for her cauldron. The Morrígan or "Phantom Queen" was the Irish goddess of destiny, death and battle. She would appear as a raven or crow and was the keeper of fate and dispenser of prophecy.

It Is NOT the Sword!

by Michael R. Burch

This poem illustrates the strong correlation between the names that appear in Welsh and Irish mythology. Much of this lore predates the Arthurian legends, and was assimilated as Arthur’s fame (and hyperbole) grew. Caladbolg is the name of a mythical Irish sword, while Caladvwlch is its Welsh equivalent. Caliburn and Excalibur are later variants.

“It is not the sword,

but the man,”

said Merlyn.

But the people demanded a sign—

the sword of Macsen Wledig,

Caladbolg, the “lightning-shard.”

“It is not the sword,

but the words men follow.”

Still, he set it in the stone

—Caladvwlch, the sword of kings—

and many a man did strive, and swore,

and many a man did moan.

But none could budge it from the stone.

“It is not the sword

or the strength,”

said Merlyn,

“that makes a man a king,

but the truth and the conviction

that ring in his iron word.”

“It is NOT the sword!”

cried Merlyn,

crowd-jostled, marveling

as Arthur drew forth Caliburn

with never a gasp,

with never a word,

and so became their king.

Originally published by Songs of Innocence, then by Romantics Quarterly, Neovictorian/Cochlea and Celtic Twilight

A VERY BRIEF TIMELINE OF IRISH POETRY

All dates are AD unless otherwise indicated and some dates are approximations (or wild guesses).

1268 BC (?) — “The Song of Amergin” is discussed in detail after this timeline.

521 — The birth of Saint Columba (521–597), who founded an important abbey on Iona and has been credited with three surviving medieval Latin hymns. He was born Colmcille ("Church Dove") in Gartan, northern Ireland.

530 — The birth of Dallán Forgaill, a blind Irish poet who is said to have written Amhra Coluim Cille in archaic Old Irish, in honor of Saint Columba. He is also credited with writing Rop Tú Mo Baile ("Be Thou My Vision").

566 — Saint Gildas is asked by Ainmericus, high king of Ireland, to restore order to the church in Ireland. Gildas becomes a missionary, building churches and establishing monasteries. Irish monasteries would play an important role in preserving literature during the Dark Ages.

600 — Possible date for early Irish saga literature. Around this time much of the main island is speaking Anglo-Saxon English.

620 — Vikings begin invasions of Ireland and will eventually take much of it over.

627 — The birth of Adomnán (c. 627–704) in Northern Ireland. His Vita Columbae ("Life of Columba") would be the first biography written in Britain.

700 — Tochmarc Étaíne ("The Wooing of Étaín/Éadaoin") is an early text of the Irish Mythological Cycle featuring characters from the Ulster Cycle of Kings that is preserved in the Lebor na hUidre (c. 1106) and Yellow Book of Lecan (c. 1401). It has been cited as a possible source for the Middle English Sir Orfeo.

731 — Bede writes The Ecclesiastical History of the English People in Latin. He notes: "At the present time, languages of five peoples are spoken in the island of the Britain ... English, British, Irish, Pictish and the Latin languages."

1250 — Ich am of Irlaunde ("I am of Ireland") is one of the first rhyming poems to mention Ireland.

I am of Ireland (anonymous Medieval Irish lyric, circa 13th-14th century AD)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I am of Ireland,

and of the holy realm of Ireland.

Gentlefolk, I pray thee:

for the sake of saintly charity,

come dance with me

in Ireland!

Ich am of Irlaunde,

Ant of the holy londe

Of Irlande.

Gode sire, pray ich the,

For of saynte charité,

Come ant daunce wyth me

In Irlaunde.

The Medieval poem above still smacks of German, with "Ich" for "I." But a metamorphosis was clearly in progress: English poetry was evolving to employ meter and rhyme, as well as Anglo-Saxon alliteration. And it's interesting to note that "ballad," "ballet" and "ball" all have the same root: the Latin ballare (to dance) and the Italian ballo/balleto (a dance). Think of a farm community assembling for a hoe-down, then dancing a two-step to music with lyrics. That is apparently how many early English poems originated. And the more regular meter of the evolving poems would suit music well.

1580 — Edmund Spenser moves to Ireland, where he will meet and become friends with Walter Ralegh. However, many natives would see them as part of a military occupation and agents of English imperialism…

1598 — Edmund Spenser's castle at Kilcolman is burned by Irish forces opposed to English dominance; according to Ben Jonson, one of Spenser's children perished in the blaze.

1667 — The birth of the Anglo-Irish poet Jonathan Swift (1667-1745). Swift was born in Dublin, but "insisted on his Englishness." He has been called the greatest prose satirist in the English language and is less well known for his poetry today.

1679 — The birth of Thomas Parnell (1679-1718), an Anglo-Irish poet and clergyman who has been called one of the "graveyard poets" along with Thomas Gray and Edward Young, among others.

1699 — Jonathan Swift becomes vicar of Laracor and later dean of St. Patrick's, Dublin. However, he considered life in Ireland to be exile.

1813 — Thomas Moore writes the popular song "The Last Rose of Summer" which appears in his Irish Melodies.

1854 — The birth of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), an Anglo-Irish poet, playwright, novelist, wit and "quintessential aesthete."

1856 — The birth of the Anglo-Irish writer and playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950).

1865 — The birth of the consensus greatest Irish poet, William Butler Yeats (1865-1939).

1882 — The birth of the Irish poet, playwright and novelist James Joyce (1882-1941).

1889 — William Butler Yeats publishes The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems. Yeats meets and falls in love with the Irish nationalist and revolutionary Maud Gonne.

1896 — The birth of the Irish poet Austin Clarke (1896-1974).

1904 — The births of the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh (1904-1967) and the Anglo-Irish poet C. Day-Lewis (1904-1972), the father of the actor Sir Daniel Day-Lewis.

1913 — "Danny Boy," a ballad written by English songwriter Frederic Weatherly is set to the Irish tune of the "Londonderry Air."

1922 — William Butler Yeats becomes a senator of the Irish Free State.

1928 — The birth of the Irish poet Thomas Kinsella (1928-).

1995 — Seamus Heaney wins the Nobel Prize for Literature.

THE SONG OF AMERGIN: THE GENESIS OF IRISH POETRY

The "Song of Amergin" and its origins remain mysteries for the ages. The ancient poem, perhaps the oldest extant poem to originate from the British Isles, or perhaps not, was written by an unknown poet at an unknown time at an uncertain location. The unlikely date 1268 BC was furnished by Robert Graves, who translated the "Song of Amergin" in his influential book The White Goddess (1948). Graves remarked that "English poetic education should, really, begin not with Canterbury Tales, not with the Odyssey, not even with Genesis, but with the Song of Amergin." Recounted in the Leabhar Gabhála (The Book of Invasions), the poem has been described as an invocation, as a mystical chant, as an affirmation of unity, as sorcery, as a creation incantation, and as the first spoken Irish poem. I have also seen it titled "The Rosc of Amergin" with a rosc being a war chant or incantation. A sort of magical affirmation to give one power over one’s enemies.

The Song of Amergin (I)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I am the sea blast

I am the tidal wave

I am the thunderous surf

I am the stag of the seven tines

I am the cliff hawk

I am the sunlit dewdrop

I am the fairest of flowers

I am the rampaging boar

I am the swift-swimming salmon

I am the placid lake

I am the summit of art

I am the vale echoing voices

I am the battle-hardened spearhead

I am the God who inflames desire

Who gives you fire

Who knows the secrets of the unhewn dolmen

Who announces the ages of the moon

Who knows where the sunset settles

In my translation above, I have deliberately worded the last four lines so that they can be either affirmations, or questions, or both. There are longer versions of the poem, but this is the version that strikes me as having the strongest ending, so I'm going to stick with it as my personal favorite. I will follow this translation with a second translation, then with an original poem I wrote under the influence of the ancient song.

The Song of Amergin (II)

a more imaginative translation by Michael R. Burch, after Robert Bridges

I am the stag of the seven tines;

I am the bull of the seven battles;

I am the boar of the seven bristles;

I am the flood cresting plains;

I am the wind sweeping tranquil waters;

I am the swift-swimming salmon in the shallow pool;

I am the sunlit dewdrop;

I am the fairest of flowers;

I am the crystalline fountain;

I am the hawk harassing its prey;

I am the demon ablaze in the campfire;

I am the battle-hardened spearhead;

I am the vale echoing voices;

I am the sea's roar;

I am the surging sea wave;

I am the summit of art;

I am the God who inflames desires;

I am the giver of fire;

Who knows the ages of the moon;

Who knows where the sunset settles;

Who knows the secrets of the unhewn dolmen.

Translator's Notes: I did not attempt to fully translate the longer version of the poem. I have read several other translations and none of them seem to agree. I went with my grokked impression of the poem: that the "I am" lines refer to God and his "all in all" nature, a belief common to the mystics of many religions. I stopped with the last line that I felt I understood and will leave the remainder of the poem to others. Amergin's ancient poem reminds me of the Biblical god Yahweh/Jehovah revealing himself to Moses as "I am that I am" and to Job as a mystery beyond human comprehension. If that's what the author intended, I tip my hat to him or her, because despite all the intervening centuries the message still comes through splendidly. If I'm wrong, I have no idea what the poem is about, but I still like it.

The Song of Amergin

an original poem by Michael R. Burch

He was our first bard

and we feel in his dim-remembered words

the moment when Time blurs . . .

and he and the Sons of Mil

heave oars as the breakers mill

till at last Ierne—green, brooding—nears,

while Some implore seas cold, fell, dark

to climb and swamp their flimsy bark

. . . and Time here also spumes, careers . . .

while the Ban Shee shriek in awed dismay

to see him still the sea, this day,

then seek the dolmen and the gloam.

Who wrote the poem? That's a good question and all "answers" seem speculative to me. Amergin has been said to be a Milesian: one of the sons of Mil who allegedly invaded and conquered Ireland sometime in the island's deep, dark, mysterious past. The Milesians were (at least theoretically) Spanish Gaels. According to the Wikipedia page:

Amergin Glúingel ("white knees"), also spelled Amhairghin Glúngheal or Glúnmar ("big knee"), was a bard, druid and judge for the Milesians in the Irish Mythological Cycle. He was appointed Chief Ollam of Ireland by his two brothers the kings of Ireland. A number of poems attributed to Amergin are part of the Milesian mythology. One of the seven sons of Míl Espáine, he took part in the Milesian conquest of Ireland from the Tuatha Dé Danann, in revenge for their great-uncle Íth, who had been treacherously killed by the three kings of the Tuatha Dé Danann: Mac Cuill, Mac Cecht and Mac Gréine. They landed at the estuary of Inber Scéne, named after Amergin's wife Scéne, who had died at sea. The three queens of the Tuatha Dé Danann, (Banba, Ériu and Fódla), gave, in turn, permission for Amergin and his people to settle in Ireland. Each of the sisters required Amergin to name the island after each of them, which he did: Ériu is the origin of the modern name Éire, while Banba and Fódla are used as poetic names for Ireland, much as Albion is for Great Britain. The Milesians had to win the island by engaging in battle with the three kings, their druids and warriors. Amergin acted as an impartial judge for the parties, setting the rules of engagement. The Milesians agreed to leave the island and retreat a short distance back into the ocean beyond the ninth wave, a magical boundary. Upon a signal, they moved toward the beach, but the druids of the Tuatha Dé Danann raised a magical storm to keep them from reaching land. However, Amergin sang an invocation calling upon the spirit of Ireland that has come to be known as The Song of Amergin, and he was able to part the storm and bring the ship safely to land. There were heavy losses on all sides, with more than one major battle, but the Milesians carried the day. The three kings of the Tuatha Dé Danann were each killed in single combat by three of the surviving sons of Míl, Eber Finn, Érimón and Amergin.

It has been suggested that the poem may have been "adapted" by Christian copyists, perhaps monks. An analogy might be the ancient Celtic myths that were "christianized" into tales of King Arthur, Lancelot, Galahad and the Holy Grail.

The following are links to other translations by Michael R. Burch:

The Seafarer

Wulf and Eadwacer

The Love Song of Shu-Sin: The Earth's Oldest Love Poem?

The Best Poetry Translations of Michael R. Burch

Sweet Rose of Virtue

How Long the Night

Caedmon's Hymn

Anglo-Saxon Riddles and Kennings

Bede's Death Song

The Wife's Lament

Deor's Lament

Lament for the Makaris

Tegner's Drapa

Whoso List to Hunt

Ancient Greek Epigrams and Epitaphs

Meleager

Sappho

Basho

Oriental Masters/Haiku

Miklós Radnóti

Rainer Maria Rilke

Marina Tsvetaeva

Renée Vivien

Ono no Komachi

Allama Iqbal

Bertolt Brecht

Ber Horvitz

Paul Celan

Primo Levi

Ahmad Faraz

Sandor Marai

Wladyslaw Szlengel

Saul Tchernichovsky

Robert Burns: Original Poems and Translations

The Seventh Romantic: Robert Burns

Free Love Poems by Michael R. Burch

The HyperTexts

This a beautiful poem, written not with a pen, but with the heart and soul

Oh, I almost forgot: thanks for the dedication. Don't forget to include John Montague - born in Brooklyn, but as Irish as they come, and a truly great poet. In regard to his poems, I would recommend 'All Legendary Obstacles', 'Tides', 'The Same Gesture' and 'Like Dolmens Round My Childhood'.

Also, you might take a look at Michael Longley and Richard Murphy - two excellent poets by any standard.